From new facilities on the Forty Acres to partnerships around the globe, Texas Engineering alumni are building it all.

By nat levy

As the live music capital of the world, it’s fair to say we built this city (Austin) on rock and roll. But it’s also built on a foundation of innovation developed at the Cockrell School.

When our Texas Engineers leave the Forty Acres with degrees from one of the top engineering schools in the nation, their charge is simple: build new things and solve big problems.

Our alumni always answer the call. They’re making an impact locally of course, but also throughout Texas, across the country and worldwide.

They’ve built and maintained the vital infrastructure we rely on every day, whether that’s where we go to work, our daily necessities like water or the entertainment we love. They’ve made essential energy breakthroughs that have transformed regions and promise to revolutionize how we power our daily lives. And they’ve built deep science and technology partnerships in other parts of the world.

Although these leaders and entrepreneurs whom you’ll get to know shortly come from diverse backgrounds, they all converge on a key theme: collaboration. Engineering is more collaborative than ever. It must be to address the massive societal challenges of the moment.

These leaders embody collaborative spirit.

CHEAT CODE: Click on a name to skip ahead in the story.

- AUTRY C. STEPHENS, Third new engineering building in a decade

- SHAY RALLS ROALSON, Protecting and growing Austin’s water infrastructure

- DAVID BALDWIN, Oil innovator takes on next-gen energy challenges

- BRIAN FALCONER, Sphere engineer is the ultimate problem solver

- MARCO BRAVO, Strengthening the Texas-Portugal research connection

CHEAT CODE: Roll over to sneak a peek at each story… and skip ahead.

We Built This  Campus

Campus

The Forty Acres

Few people exemplify the value of an engineering education like Autry C. Stephens. The son of melon and peanut farmers, Stephens was the first in his family to go to college.

This decision changed his life, his family’s lives, and soon the lives of future generations of Texas Engineering students. After getting his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in petroleum engineering from UT, Stephens went on to become a key figure in the Texas energy industry, serving as a catalyst that made the Permian Basin a global oil and gas hub.

“My father would say, ‘With a UT degree in petroleum engineering, you are almost guaranteed success—it is a great foundation. There will be many ups and downs during life, but your education will always be with you and will never disappoint you,'” said Lyndal Stephens Greth, daughter of Autry C. Stephens and director and executive chairman of the Stephens Greth Foundation. “He was the first in his family to go to college, and that decision set everything in motion. The education he received at UT—earning both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in petroleum engineering—gave him the confidence and skills to pursue a career he was truly passionate about. He felt his education was a part of the foundation that never let him down, no matter what challenges he faced in his professional career. The University not only opened doors for him, but gave him an enduring sense of possibility, showing him that with hard work and determination, he could build a life far beyond what he imagined as a boy growing up on his family’s farm.”

Stephens, who passed away in 2024, is now fittingly building a foundation for future engineers as the namesake of the Cockrell School’s latest facility, the Autry C. Stephens Engineering Discovery Building (ACS). Opening later this year, the 210,000-square-foot building will be home to the Hildebrand Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering, as well as the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering.

ACS marks the third new engineering building on the Forty Acres in a decade. The Gary L. Thomas Energy Engineering Building opened in 2021, and the Engineering Education and Research Center opened in 2017.

“My father would see this building as far more than a tribute to his name—it would represent a living legacy of opportunity and transformation,” Lyndal Greth said. “He always believed that the greatest measure of success was in opening doors for others, and this building will do exactly that. To him, its true significance would lie in the students and faculty it empowers: those who walk in uncertain, searching for their path, and leave with the confidence to shape the future.”

Stephens made his mark by amassing drilling rights on more than 350,000 acres of land in the oil-rich Permian Basin and holding them for decades until the time was right. (editor’s note: more on that technological breakthrough further down)

His unique combination of risk-taking and discipline enabled him to weather the industry’s boom-and-bust cycles and maintain momentum. Shortly before his death, Stephens secured the future for his family and employees by selling his company, Endeavor Energy Resources, to another Texas-based company, Diamondback Energy, creating the third-largest oil and gas producer in the region.

He even became a reality TV star when his company at the time, Big Dog Drilling, served as the focus of the five-season series Black Gold.

Now, his family is investing in the communities that enabled Stephens’ success. And it wouldn’t have happened without that degree and his entrepreneurial spirit.

“Your degree will open many doors, but it is just a license to learn. The world changes rapidly, and you must stay open to new ideas and technology developments. Change jobs if necessary, in order to find work that you enjoy. The history of the oil industry is full of stories of people making and losing fortunes several times over. Don’t let fear of failure keep you from following your dream.”

— Autry C. Stephens, from a 2011 interview

We Built This  City

City

Austin's Infrastructure

Austin Water, the city’s water and wastewater utility, serves 1.17 million retail and wholesale customers across a 538-square-mile service area. More than 4,000 miles of water distribution pipes run beneath city streets, and a trio of treatment plants purifies more than 150 million gallons of water per day.

Texas Engineer Shay Ralls Roalson is in charge of all this critical infrastructure. The civil engineering alumna became the first woman to lead the utility in 2023 after serving as assistant director of engineering services for three years.

This wasn’t her first go-round with Austin Water. She interned there while in graduate school, studying under professor Desmond Lawler. She conducted her thesis experiments on water softening—the process of removing minerals like calcium and magnesium from water—using water from its treatment plants.

UT faculty and students have partnered with Austin Water for years. Roalson recalls a time when Lawler visited the plant and launched into an on-the-fly training course for process engineers. Following major flooding in 2018 that overwhelmed the treatment plants, teams from UT and engineering firms replete with Texas Exes collaborated with Austin Water to refine treatment processes, helping the plants rebound from the disaster.

Shay Ralls Roalson (center) with Austin Water staff. Courtesy Austin Water.

In 2023, environmental engineering professor Lynn Katz led a review of Austin Water. And Austin Water is part of a research partnership between the city of Austin and UT.

“There are a lot of Texas Exes in the water business in Austin,” Roalson said. “It’s a very collaborative, tight-knit community working together to solve an enormous challenge of making sure more than 1 million people have access to clean water all the time.”

Leading a water utility in one of the biggest cities in the country in a hot, dry climate comes with a lot of pressure, no pun intended. Because water systems are in constant need of upgrades, some piece of the puzzle will always be outdated or in need of repair. And Austin Water’s 1,400 employees are working 24/7 to operate and maintain this critical infrastructure.

Implementing a 100-year water resource plan is a key part of her job. Austin Water just finished up the first five-year update to its Water Forward plan.

Plans that look out decades into the future are a response to the biggest challenge the utility faces: uncertainty on many fronts. Austin is growing, and it has been for decades. The climate is changing, and no one knows what that will mean for water management.

“We can no longer look backward to look forward. That’s why it’s so important for our planning to be adaptive to changing conditions.”

— Shay Ralls Roalson

But Roalson has faith that advanced planning, combined with the knowledge and passion of Austin Water staff will allow them to mitigate these challenges.

Roalson’s confidence in her team and its plans may not have materialized without her time at UT. In addition to the technical knowledge and problem-solving skills she gained, she also developed the confidence to become an expert.

A presentation she gave as a graduate student at the annual conference of the American Water Works Association provides a perfect example of coming into her own as an expert. As she prepared to present a paper on advanced water softening, she sat on stage between two experts in the field, with the authors she cited in her paper littered throughout the audience.

“In the middle of my presentation, I had a light bulb moment,” she said. “These were incredible experts, all of them renowned in their field, but nobody knew my work better than I did. I learned to trust my ability to identify a problem, quantify the problem and then systematically take it apart to figure out each piece and come to a solution.”

We Built This  State

State

Texas' Energy Empire

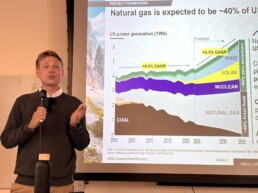

Want to know where the Texas energy industry is going? Take a look at David Baldwin.

He was instrumental in the creation and adoption of horizontal drilling in the 1980s and ‘90s, a concept that galvanized the U.S. shale revolution. Now he’s using the same tactics to advance next-generation energy technologies, such as clean electricity and batteries.

A baseball player at UT and son of an engineer, Baldwin was influenced by his father and close friends on campus, including future NFL offensive lineman Doug Dawson, to pursue the challenging field. Early in Baldwin’s career, with a supportive boss who identified his entrepreneurial spark, he was tasked with figuring out how to take an offshore drilling technique and expand it.

The technique involves drilling down vertically, then making a sharp turn to create a 90-degree angle. This would open up access to horizontal fractures that resembled long hallways filled with oil.

Baldwin knew he couldn’t solve such a big problem on his own. Like baseball, he sees engineering as a team sport.

“I was not the most technical engineer, but I’m proud that I was able to find the people who are the best in the world in what they do, and we all came together in one place to figure it out. Many of them were field people, not engineers. They were the world’s best drill bit specialist or the world’s best navigational specialist, and I brought them all to Texas to hash it out.”

— David Baldwin, on the challenge of solving horizontal drilling

Together, this group developed the idea behind horizontal drilling. These experts took what they learned back to their companies, implemented it and continued to improve it.

Baldwin’s next step took him to the world of investing at SCF Partners, where he invested in and helped build oil and gas and other energy service companies around the world. In the last decade, Baldwin has broadened his focus to next-generation energy technologies. He started a group in 2022 called OpenMinds, with a simple goal: “more energy, less emissions, fast.”

In an attempt to replicate his experience with horizontal drilling, OpenMinds has assembled more than 100 climate and energy experts to tackle this significant problem. He believes that Texas, with its rich history of oil and gas innovation and its nation-leading renewable energy workforce, is well-positioned to drive the world’s next energy and climate revolution.

“You don’t have to be an energy person or a climate person; we can solve both of these challenges at the same time,” Baldwin said. “And no other university can match UT’s expertise across these disciplines to be a leader in both energy and climate technology.”

We Built This  Country

Country

The Sphere, USA

Growing up in St. Louis, Brian Falconer used to look out the window of his high school classroom and see the Gateway Arch. Little did he know that just a few years later, he’d get a job at the company that engineered that iconic structure.

In his 35 years at that company, Severud Associates, where Falconer is now a principal, he’s had the opportunity to engineer many more iconic structures. Falconer led the engineering of celebrated projects in his firm’s New York City home base, including the redevelopment of the original Penn Station, now known as the Moynihan Train Hall, and ongoing work with the American Museum of Natural History and Museum of Modern Art. He’s also worked on higher education facilities at the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan and more.

Brian Falconer at a construction site and some of the other projects he worked on over the years. Photos Courtesy Brian Falconer.

Falconer is the guy architects call on to solve impossible challenges. That’s a big reason why he was the engineer of record on the eye-catching Las Vegas Sphere.

The brain-child of Madison Square Garden and New York Knicks owner James Dolan, the Sphere was built on a foundation of challenges. How can a big sphere serve as an entertainment venue? How can the outside function as a giant video board? And, most importantly, what does it take to construct the world’s largest spherical structure?

Falconer compared the construction to a giant erector set, with large pipes linked by cast connections in a series of hexagons. The team built the bottom from the ground up, until they reached the hemisphere, where a tall shoring tower was installed in the center.

One of the largest roller cranes on the planet erected the keystone at the crown. The rest of the structure was then built from the crown down.

There was little margin for error in this challenging project.

“In a typical building, you make everything square and it fits together in a very simple way,” Falconer said. “There’s a lot of play in the joints, so if they’re not perfect, they can be fixed. In this case, everything had to go perfectly together like a very complex machine to keep that geometry together.”

Falconer relishes being the ultimate problem-solver. But he doesn’t do it alone. In fact, he still relies on friends he made at UT, where he got his master’s in civil engineering.

He recalled a time he investigated why an acrylic case for squids at the American Museum of Natural History cracked. Everything seemed fine structurally, so he called up Paul Tikalsky, a former dean of Oklahoma State University’s College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology who Falconer sat next to when they were both students at UT.

Together, they discovered the culprit: mismatched materials. The acrylic case was bent at too low of a temperature, creating a prestress. The alcohol preservative for the squid attacked the prestress and caused the cracks.

This case exemplifies Falconer’s approach to engineering. It centers around tenacity, collaboration and trying new things.

“You’re not going to change the world just doing what’s been done for the last 100 years and never doing anything different. As engineers, we’re not always the ones to branch out and discover something completely new, but we take all these things that other people have figured out and assemble them into something new and unique.”

— Brian Falconer

We Built This  World

World

Global Community

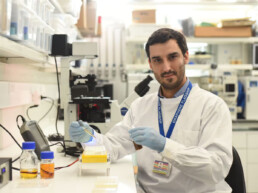

UT is a household name in Portugal these days, and Marco Bravo is a big reason why.

He is the executive director of the UT Austin Portugal program, one of three science and technology partnerships between Portugal and U.S. universities. The program has been immensely successful as it approaches its 20th anniversary in 2027, and it was just renewed for another five years.

Two startups that went through the program became $1 billion “unicorns,” and another startup founder went on to win a Nobel Prize. And it has been the most active of the three Portugal programs—the other two partners are Carnegie Mellon University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology—in supporting startup growth and impact.

Marco Bravo at a UT event.

The UT Austin Portugal program shares several similarities with the other two, including regular calls for research projects to support, which are the bread and butter of these partnerships. Relying on his entrepreneurial background, Bravo has pushed a series of initiatives that he calls “outside the box,” which set the UT program apart.

The primary example is the Global Startup Program, which launched as an experiment in 2014 and is currently being revamped to add new initiatives. The program helps Portuguese deep technology startups internationalize by connecting them with networking, mentorship and capital opportunities at innovation ecosystems in Texas and the rest of the U.S. It focuses on product-market fit and hands-on business development actions to achieve tangible revenue-making deals for companies.

“These initiatives can be very risky because they’re new and hard to implement, just like a startup. But when they work, they’re huge successes.”

— Marco Bravo

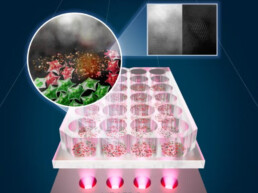

UT professor Jean Anne Incorvia and University of Porto professor Artur Pinto developed a new light-base cancer treatment that can neutralize cancer cells while shielding healthy cells. CREDIT (portrait of Artur): University of Porto

The proof of impact is there. The UT Austin Portugal program has returned $40 for every $1 invested by the Foundation for Science and Technology, the Portuguese equivalent of the NSF, a total economic impact of $130 million, according to a 2016 independent study.

Governments change. New leaders cycle in and out. Bravo and the UT Austin Portugal team consistently find ways to demonstrate the program’s benefits.

“Today, everybody knows about UT in Portugal,” Bravo said. “It’s not because of just general name recognition; it’s because of all the great things this partnership has done for the country.”

WHAT ARE YOU BUILDING?

Are you an alum building something we should know about? We want to hear your story.