An Essay By Tyson Smiter

As a Black engineer, I tend to stray away from history. It’s not that I don’t recognize the value of the past, I just don’t prize imperfect sciences. You see, history is incapable of telling complete stories, and far too often, Black people’s accomplishments and perspectives are among the historical elements that come up missing. Society waters down the brilliant hues of Black achievement, they redact the markings of meticulous, hard-fought progress, and white-out the bitter resistance of oppression. Decades and centuries later, the same marginalized communities who bore the brunt of discrimination are the ones obligated to keep Black stories alive. Yes, we’re well-equipped to tell these stories. Yes, we don’t shy away from the pervasive, horrifying racism they lay bare; but ultimately, we’re the only ones who care enough to capture, cultivate, and propagate Black history.

Thus, I will tell the story of John W. Hargis — The University of Texas at Austin’s first Black undergraduate student, first Black student at UT to receive an engineering degree, founder of the Epsilon Iota Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, first chairman of the Texas Exes’ Black Alumni Task Force and so much more. Hargis’ excellence, magnanimity, resilience, and lifelong commitment to The University of Texas at Austin are awe-inspiring. Mr. Hargis is my personal hero and one of the most impactful individuals to ever call the Forty Acres home.

Earned, Not Given — A Relentless Fight for Integration

In 1953, John Willis Hargis graduated valedictorian of segregated Anderson High School in Austin. Aspiring to continue his education, Hargis enrolled at Morehouse College, a renowned institution for Black students in Atlanta. The University of Texas at Austin was not an option for Hargis. Undergraduate education at UT was reserved for white students. Any Black undergraduate applicant to UT would instead be referred to a public institution for Black students.

The next year, in 1954, the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education struck down the doctrine of separate but equal. On the heels of this historic ruling, seven Black students, Hargis included, applied and were admitted to UT. Their achievement was painfully short-lived. In the four months between the May ruling and the September start of the fall semester, UT Dean of Admissions H.Y. McCown worked alongside the university administration to devise a strategy to exclude as many Negro undergraduates as possible.

a In September 1954, the very day before course registration for the fall semester, McCown’s plan took effect, and all seven admitted Black students were informed that their acceptance to UT Austin was revoked.

McCown’s devious policy required Black undergraduates to fulfill first-year core requirements at a public Texas university for Black students. Hargis, a transfer applicant to UT’s chemical engineering program, had already completed first-year coursework at Morehouse, so he challenged the applicability of the policy. His appeal was futile. Barred from registration, Hargis was sent to Prairie View A&M, an institution for Black students outside of Houston. There, Hargis found few curriculum offerings that he had not previously studied at Morehouse. He enrolled in an advanced course load for the fall and applied once more to UT for the spring semester — an application that was denied. Shut out yet again, Hargis devoted himself to his education at Prairie View A&M in the spring of 1955, all the while remaining vigilant for an opportunity to secure admission to UT.

In the summer of 1955, Hargis seized an unlikely opening. That May, the Supreme Court announced a second ruling in Brown v. Board of Education II, creating a timeline for desegregation. In a response illustrative of chasmic hatred and the ideology of white supremacy, universities in the South scrambled to enact measures that would limit a surge of Black applicants. One month after the court’s decision, The University of Texas Board of Regents announced that integration on campus would not take place until the fall of 1956, more than one year later. Alongside integration, the University of Texas introduced its first admissions test ever. With these measures in place, Board of Regents Chairman Tom Sealy went so far as to pledge that he, an attorney, would personally oppose in court any attempt at integration earlier than the fall of 1956. Ironically, the attention around slowing desegregation obscured Hargis’ third UT application from the public eye. After two semesters at Prairie View A&M, Hargis had completed the core requirements to pursue a chemical engineering degree, and there were no means that UT could employ to deny him admission. In June 1955, John W. Hargis was admitted, for the second time, to The University of Texas at Austin.

Yet again, admission alone did not insulate Hargis from stubborn opposition to his enrollment. This time around, Hargis made it to registration before his inclusion on the Forty Acres was disputed. When he traveled to campus to enroll in courses for the summer session, Hargis was sent to meet directly with UT President Logan Wilson. Wilson noticed that Hargis was unaccompanied by an attorney from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and tried to impede Hargis’ registration by discrediting his physics prerequisites, citing Prairie View A&M as an inferior university. Standing tall in the face of President Wilson’s dishonesty, Hargis responded emphatically, asserting that it was not his choice to attend Prairie View A&M but that it was UT’s decision, as their prior mandate had sent him there. Faced with an adamant Hargis, President Wilson conceded and allowed the transfer of the physics credits.

One year after his original acceptance had been revoked, Hargis became the first Black undergraduate student to enroll at The University of Texas at Austin. Mr. Hargis’ journey through rejection, obstruction, and exile is a testament to his remarkable grit. He fought ardently for the chance to pursue a world-class engineering degree, and in doing so, facilitated UT’s earliest step toward racial equity in undergraduate education. Our campus today owes John W. Hargis an immense debt for his resilience in the face of prejudice, and we’ll come to see that his odyssey was far from finished.

Agony, Opportunity, and Change — The Forty Acres Experience

Hargis began studying chemical engineering at UT during the summer of 1955, alongside two other Black undergraduates from Prairie View A&M. The PV three,

as I like to call them, became Longhorns more than a year before UT’s fall 1956 integration target and, as such, university policies governing undergraduate integration were not yet in place. Amidst a backdrop of heavy opposition to desegregation in the state, this policy void left the door wide open to discrimination.

Hargis and other early Black students endured inhumane treatment. They weren’t permitted to live on campus, play sports, join organizations, or attend local venues like restaurants and theatres. Black students during this period were often excluded or outright ignored by faculty, students, and staff, making group projects, participation grades, and comprehensive academic success essentially nonviable. Black students lived under a perpetual threat of violence from individuals, institutions, and organized groups seeking to intimidate and assert the notion of Black inferiority. Faced with social exile, palpable racial tension, and dehumanizing treatment, two of the PV three

withdrew before summer’s end, leaving Hargis as UT’s sole Black undergraduate.

In the fall of 1955, two more Black students enrolled at UT, pushing the Black undergraduate population back to three. It wouldn’t last. Again, the maelstrom of bigotry, apathy, and community-imposed solitude proved too much. That year, one Black student would suffer a psychological breakdown and subsequently withdraw. With formal integration at UT many months away, the two remaining undergraduates, Hargis and Norcell Haywood, relied on each other heavily for support. As they grew closer, hostility toward integration soared around the state, bringing into sharp focus the danger that Black integrators faced.

The spring of 1956 imperiled Black students across Texas as anti-integration sentiment erupted. At Texarkana Junior College and Lamar University, lawless mobs attacked Black students to keep them off campus. All the while, Texas Rangers stood by and watched, following orders from the Governor himself to maintain order,

b but not to assist in integration. Unrest during this period was enabled, if not endorsed, by political leadership. A total of 96 Southern congressmen and senators signed a Southern Manifesto

fiercely opposing desegregation. This Manifesto labeled the Brown v. Board of Education ruling as a clear abuse of judicial power

c and claimed that it was destroying the amicable relations between the White and Negro races.

c One notable manifesto backer, Senator Price Daniel, had represented UT before the Supreme Court in Sweatt v. Painter, arguing for the university’s legal right to automatically decline Black applicants. Daniel would later become governor of Texas in 1957, during Hargis’ sophomore year. Amidst turmoil and deep-seated intolerance on campuses statewide, Hargis felt that he couldn’t afford to let down his guard on or around the Forty Acres. He closed the spring of 1956 both eager and apprehensive for formal integration coming in the fall. The influx of Black students would either realize a progressive breakthrough or incite a sectarian resurgence.

As UT had promised, larger scale integration began in the fall of 1956 when 110 Black freshmen and undergraduate transfers enrolled. The university’s new admissions test, introduced as a measure alongside desegregation, disproportionately stymied Black applicants. 19.6% of Black students passed in 1956, compared to 45.6% of white students, and evidence suggests that this bias was intentional. The exams largely functioned to limit Black enrollment. An advisor to University President Logan Wilson later acknowledged as much, noting that UT’s reasoning for delaying integration until 1956 was to facilitate the implementation of such admissions testing. These screenings were purportedly administered equally to all regardless of racial origin,

d but privately, UT Regents insisted upon segregated testing. Nevertheless, the boom from two to 110 Black students marked a step toward an implacable Black presence on campus and laid the foundation for the Black community at UT. Hargis’ lengthy tenure relative to newly enrolled Black students positioned him as a leader, mentor, and voice of reason within UT’s developing Black culture. Under the newfound stability and guidance of veteran students like Hargis, the perception of Black undergraduates on campus began shifting from undesirables to contributors, pioneers, and world-changers.

During Hargis’ third year at UT, he began leveraging religion as a common ground to connect with a largely apathetic student body. In the fall of 1957, he earned his first formal leadership role serving on the cabinet of the Wesley Foundation, a Methodist group. That same year, Hargis was named Vice President of the newly formed University Religious Foundation. In attaining these executive positions, he cemented himself not only as an influential presence on the Forty Acres, but also as a masterful collaborator and empathizer.

Hargis (far left) at a meeting of the Wesley Foundation, a Methodist group for which he served in a leadership role. Photo from the 1958 Cactus Yearbook.

Through Hargis’ involvement in existing campus groups, he recognized the immense value that a uniquely Black organization could provide UT students. Hargis believed that fraternities provided distinct advantages to members through both social and academic support. At a time when UT’s Greek organizations were ardently opposed to Black membership, Hargis sought to establish a chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, Inc., the national fraternity for African American men, on campus. The idea was poorly received and UT administrators refused to recognize the fraternity. Thus, the group was forced to function as a pre-fraternal colony, Alpha Upsilon Tau, from April 1958 to March 1960, until they had hosted enough elaborate events to move the Inter-fraternity Council into granting them recognition. Though Hargis had graduated by the time Alpha Phi Alpha obtained its charter at UT Austin, the nearby chapter at Huston-Tillotson University awarded him Alpha Man of the Year in honor of his initiative and impact.

The Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity that Hargis established at UT. Photo from the group’s 1958 Sphinx newsletter.

Three schools, four applications, and six grueling years after Hargis began his undergraduate education, he emerged triumphant. In January of 1959, John Willis Hargis became the first African American to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering — and in chemical engineering specifically — from The University of Texas at Austin.

He overcame countless challenges in pursuit of his degree. Although Hargis was a former valedictorian, the inequity of segregated schooling left him facing a steep collegiate learning curve. He braved discrimination day in and day out, he committed himself to success at a university where he was not wanted, and his sacrifice formed the foundation for tens of thousands of Black students and alumni who cherish the Forty Acres today. At only 24 years old, Hargis, the Longhorn graduate, was already the giant on whose shoulders every future student at The University of Texas at Austin would stand. Still, however, Mr. Hargis had further contributions in store for our campus.

Mind of an Engineer, Heart of a Longhorn — Life After UT

When John W. Hargis graduated in 1959, career prospects were scarce for Black engineers. Hargis, a proven leader, collaborator, and go-getter with unrivaled strength in the face of adversity, fielded only two job opportunities — a teacher at a Black college or a temporary role as a process engineer. He chose industry, opting for a space where he could continue breaking down barriers. Hargis was well-equipped for professional success and his career quickly advanced. In his first role, he developed a chemical manufacturing facility that would remain in use for the next 26 years. In 1961, he switched companies and received his first patent. Three years later, Audio Devices, Inc. lured Hargis to Connecticut. There, he would earn an MBA, win his companies’ President’s Award and gain promotion to plant manager. In 1973, Hargis was named Vice President of Manufacturing at Capitol Records, Inc. where he oversaw a 599-employee manufacturing operation generating over $30 million in annual revenue.

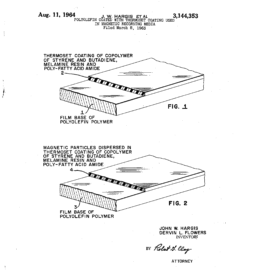

From the U.S. Patent Office, a drawing of Hargis’ magnetic recording tape, for which he was awarded a patent in the early 1960s.

Hargis was also heavily involved in social organizations throughout his career. Between 1972 and 1976, he served as President of the New Canaan chapter of the NAACP, president of the Interchurch Services Committee, President of the West Side Development Corporation, and Treasurer and later Chairman of the Democratic Town Committee. He even ran for Mayor of New Canaan before becoming the first Black appointee to the New Canaan Board of Finance. A model citizen and staple within his community, Hargis’ contributions were recognized in editions of Community Leaders and Noteworthy Americans, Black Leaders in America, and Who’s Who in the East.

As his professional and social lives flourished, Hargis maintained an intimate bond with UT Austin as an alumnus. In 1972, he applied for lifetime membership to the Ex-Students Association. In that application, Hargis spoke of his dreams to become president of a major corporation and then to return to the Forty Acres as a professor in engineering or business. He was doing well to realize those aspirations, until two major heart attacks, diagnosis of a heart ailment, and open-heart surgery pushed him to retire at only 46 years old. Reevaluating his health and life plan, Hargis returned to Austin to fully embrace the UT community sooner, rather than later.

Hargis is recognized at an Alpha Phi Alpha event in 1976. Photo from the group’s Sphinx newsletter.

Back in Austin, Hargis was shocked at how slowly Black involvement on campus and in alumni affairs had advanced. In 1982, 23 years after Hargis’ graduation, only 1,311 Black students enrolled at UT, about 2.7% of the student body. Black students were drastically underrepresented within engineering, made up an even smaller percentage of student organization members, and, upon graduation, rarely joined the Ex-Students Association. Seeing these trends, Hargis disobeyed his doctor’s orders and got to organizing. Alongside UT administrators, Hargis developed strategies to improve undergraduate life and enhance Black student retention. To engage alumni, Hargis successfully proposed a Black Alumni Task Force of the Ex-Students Association (today, the Texas Exes), becoming the group’s first chairperson in 1985. As chair, he outlined two goals: to begin healing the wounds of the university experience for Black alumni and to increase Black participation in the alumni network. His efforts and leadership would usher in 500 Black alumni as Ex-Students Association members and 50 more as lifetime members.

In October 1986, Hargis’ influence in the Longhorn community grew so large that UT President William H. Cunningham appointed him Special Assistant to the President for Minority Affairs. Following this formal recognition, Hargis described himself on Cloud Nine.

d That same euphoria, pride, and commitment to the university kept him hard at work, even as his health faltered. Hargis continued fighting to facilitate a better student experience for the next month. On Tuesday, November 12, 1986, he was working diligently in the office; on Wednesday, November 13, 1986, Mr. Hargis was found unresponsive in his home.

The University of Texas at Austin honored Hargis with a memorial service one week later. Those who knew him spoke reverently of his character and stellar achievements. President Cunningham exalted Hargis’ commitment to improving and strengthening a university that has made his path very difficult.

d Later that day, the University Students Association and the National Society of Black Engineers requested that the newly completed Chemical and Petroleum Engineering Building (CPE) be named for Hargis. President Cunningham instead suggested that the Admissions and Employment Center, located south of MLK Boulevard, become John W. Hargis Hall. In February 1987, after waiving a rule that prohibited naming a building for someone until five years after that person’s death, the Board of Regents approved the naming of John W. Hargis Hall. Later that spring, both the College of Engineering and the Black Alumni Task Force of the Texas Exes launched awards in honor of Hargis — the John W. Hargis Endowed Presidential Scholarship and the John W. Hargis Memorial Scholarship, respectively. Today, both scholarships champion Hargis’ legacy in facilitating Black undergraduate opportunity, inclusion, and achievement on the Forty Acres.

When Hargis was only a teen, the University of Texas community worked tenaciously to exclude him. Yet somehow, despite the trauma the university had caused him and many of his peers, Mr. Hargis still felt most at home as a student and alumnus in the College of Engineering.

d It is only fitting then that he returned to a more welcoming Forty Acres in the final years of his life. Hargis was a superhero, deserving of massive praise and renown. He moved mountains in all spheres of life with his boundless initiative, resolve, and compassion. Until his last day, he dedicated himself to excellence and service toward the things that mattered to him most — family, community, equity, and, fortunately for us, UT Austin.

In Closing

The name John W. Hargis deserves immediate recognition in the mind of every student or alumnus of The University of Texas at Austin. His inspiring and triumphant story should reverberate across campus, amplifying semester after semester, class after class. In the face of unjustifiable prejudice, his persistence opened doors, enabling progress for the marginalized. While Black life was met with apathy, Hargis’ wisdom fostered communities of unignorable world-changers. And when his own health began to decline, Hargis’ courageous leadership and tenacity brought newfound hope for justice to the Forty Acres. I am honored to share this glimpse of Mr. Hargis’ life with you, and I hope that together we can continue his struggle to realize racial equity at UT Austin. The responsibility rests on each of us to keep this story alive, and to incorporate Hargis’ strength, empathy, and selflessness into our lives.

a TO EXCLUDE AS MANY NEGRO UNDERGRADUATES AS POSSIBLE

: Brown v. Board of Education and the University of Texas at Austin, Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. cambridge.org/core/journals/du-bois-review-social-science-research-on-race/article/abs/to-exclude-as-many-negro-undergraduates-as-possible-brown-v-board-of-education-and-the-university-of-texas-at-austin/4BBDD1A06E3511D3111E863F47853BA2#ref063

b texasranger.org/texas-ranger-museum/history/timeline/

c thirteen.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/sources_document2.html

d Richard B. McCaslin, Hargis, John W.,

Handbook of Texas Online, accessed April 04, 2021, tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/hargis-john-w

Other sources:

- Texas State Historical Association. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 95, July 1991 – April, 1992, periodical, 1992; Austin, Texas. texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth117153/: accessed April 4, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Texas State Historical Association.

- The Texas Book Two: More Profiles, History, and Reminiscences of the University. United States: University of Texas Press, 2012.

- Richard B. McCaslin, “Hargis, John W.,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed April 04, 2021, tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/hargis-john-w

- issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/1976062041/11

- issuu.com/apa1906network/docs/195804303/23

- apa1906.net/our-history/

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_Manifesto

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweatt_v._Painter

- utexas.app.box.com/v/SHB82-83Complete

- repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/61518

- repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/

- utdirect.utexas.edu/apps/campus/buildings/nlogon/facilities/

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L.C._(Laurine_Cecil)_Anderson

- diversity.utexas.edu/integration/2014/07/overcoming-isolation-in-the-early-years-of-integration-exalton-delco-and-norcell-haywood/

- diversity.utexas.edu/integration/2015/09/precursor-stories-haywood-and-alexander/

- diversity.utexas.edu/integration/timeline/

Tyson Smiter graduated from the Cockrell School in 2020 with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering with high honors. In addition to participating in undergraduate research, internships and study abroad programs, Tyson served as President of the UT chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers for two years. He is currently a manufacturing engineer at Microsoft.

Tyson has continued to be involved with the Cockrell School after graduating. He helped to establish the John W. Hargis Lounge (inside the Engineering Education and Research Center), a student community space that will be celebrated with a grand opening event in spring 2022.