by Marty Toohey

The refugee camp stood at the foot of wooded Greek hills. Just inside the gate, along one of the high concrete walls, lay a long, narrow strip of gravel that Thomas Eichelberger and other Cockrell School students had traveled more than 6,000 miles to help turn into a playground. On this bright, brisk spring morning Eichelberger began recording terrain measurements. At the same time, Eman Zaheer turned to face what was, in all likelihood, the most unusual engineering challenge to face Cockrell students this year: keeping a group of smiling, curious, rambunctious Afghan children out from underfoot while the survey team did its work.

That was definitely not what I’m used to,

said Zaheer, a senior in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering. As an engineer, you want the one independent variable and the one dependent variable. You want to change one thing, and then have one thing change as a result. When you’re working with people, it’s never that simple.

And that’s actually a great thing.

Engineer Globally

This overseas experience in Greece, part of the Humanitarian Engineering program, exemplifies the opportunities the Cockrell School offers through its expanding menu of study abroad opportunities crafted specifically for engineers.

Study abroad programs benefit students both personally and professionally, but engineering, with its regimented academic track, often cannot accommodate a six-month gap in coursework. Engineers in training also face intense pressure to fill months not occupied by coursework with professional internships.

Such pressures led to the creation of the International Engineering Education program (IEE). To accommodate the demands of engineering education, IEE offers a variety of opportunities, many of which are shorter than other exchange programs. They typically happen during a time known as Maymester, the window between the end of spring semester and start of summer.

Nearly 500 engineering students participated in an international experience this past year. IEE aims to double that number in three years.

Want to help solve a global challenge? Manish Kumar, who teaches water resource engineering, leads a Maymester class where students travel to Kenya to develop solar-powered water filtration systems for rural villages. The four-week experience is one of more than a dozen options for students to immerse themselves before returning for a summer internship.

Or does an internship in a foreign country — where U.S.-tinged assumptions can be upended — sound more appealing? William Fagelson guides students through that learning curve during a stay in Kyoto, Japan as part of his engineering communications program. It is one of many internship-focused summer opportunities in places like Spain, South Korea and the United Kingdom. Students in these internships can see and hear how firms operate and build the professional skills to work in global teams and lead international projects.

“Hiring boards want students with international experience. Furthermore, many engineers work with policymakers and government. There are no borders for air pollution, water pollution, issues today’s engineers are passionate about solving. As engineers, you’re going to need to understand how the world operates.”

— Helena Wilkins-Versalovic, director, IEE

Japan

Michelle Alex spent eight weeks in Kyoto, a city of 1.5 million people, struck by the quiet.

That quiet made commuter train rides peaceful, so long as she and her fellow interns kept their voices down. It contributed a sense of order to walks through crowded streets, where people kept to themselves. It was evident in her boss, an architect who rarely told Alex and her fellow students what to do, or not do, as he guided them through designing a rest area for Japanese foresters working in a bamboo field.

Alex was not accustomed to such quiet. Americans are outgoing, often quick to smile or strike up a conversation or offer an opinion. Alex spent much of her childhood in India, another boisterous place. Japan, by comparison, felt different: a culture in which people prize orderliness, cohesion and, in particular, privacy.

It’s really hard to strike up a conversation with a stranger,

said Alex, a fourth-year student majoring in architecture and architectural engineering.

The quiet left many of Fagelson’s students disoriented, he said. During the engineering communications class, the 20 students discussed how to parse the indirectness that shapes so much of Japanese office life. Many found the lack of straightforward, good-job/bad-job feedback challenging. The Japanese approach can feel introverted and leave foreigners feeling like, well, outsiders. Even Fagelson, an associate professor of instruction in the Chandra Family Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and writer and researcher who has worked around the world, felt it.

“We tend to see the way things are around us, what we’re used to, as the natural way of the world. One thing that becomes apparent pretty quickly (in such courses) is that there are other ways of being, other ways of doing.”

— William Fagelson

A trip on the ever-quiet trains helped put the polite, but distant feeling into perspective for Alex. About two weeks into the trip, she and a friend in the program were returning from a day of sightseeing. A boy, perhaps six years old, grinned at them. He was with his mother and grandmother. They spoke little English. But Alex decided to strike up a conversation.

Haltingly, through Google Translate, the family told her that the boy loved her friend’s hat, a replica of the one worn by Luigi, the beloved lesser-known brother of the Super Mario Bros. video games. The family wanted to know how they were doing. Did they like Japan? Was being away from home difficult? The conversation lasted only 15 minutes or so, and the lesson itself was not surprising: curiosity and kindness are, sooner or later, reciprocated. But believing that and experiencing it, particularly in a place that feels utterly foreign, are different things.

I was just so happy after that. It reminded me there are lots of ways to connect with people,

Alex said. Even if you don’t speak the language.

Other moments of warmth seeped through the customary coolness. The foresters for whom Alex and other students were designing the rest area shared tea and snacks. Even in a culture of understatement, they showed excitement for the plan the students produced. And Alex’s supervisor, an architecture professor, cooked lunch for the students along with his wife several times. He never told them what to do, or expressed displeasure. His indirectness aimed to give them space to find their way through designing the rest stop, Alex said — to guide, not tell.

Such experiences are why Wilkins-Versalovic has made a career of study abroad programs. The perspective of living and working in a new culture opens cognitive windows

that can boost a career. The combination of internship and coursework also bolsters early resumes, enabling swifter progression up the internship-to-job ladder.

We really push first-year students to study abroad,” Wilkins-Versalovic said, “because afterward they get busier and busier.

Napoleón Nasta-Terrazas heard about the IEE industry immersion experiences shortly after arriving on campus. The first-year chemical engineering major immediately applied for Fagelson’s Kyoto trip and got in a month later. Two thoughts then occurred to him: I need to start studying Japanese, and I need to start applying for scholarships now.

There is no tuition fee for IEE’s Maymester offerings — they are included in spring tuition costs — but students must pay for housing, flights, meals, other costs, and a program fee. Still, financial aid helped defray the cost for three-quarters of the students who went on IEE trips last year. The Cockrell School also awarded 115 alumni-funded scholarships, which usually cover most or all expenses. Study abroad experiences with a service-learning component, such as helping to solve a local or regional issue, are seeing increased alumni donations, Wilkins-Versalovic said. IEE is seeking additional funding to offset the cost of the internship-based trips.

Nasta-Terrazas spent his winter break applying for scholarships and snagged enough money that only the plane tickets came from his pocket. He signed a non-disclosure agreement that prevents him from discussing much of his internship at MOLFEX, Inc., but he can say this: the company uses quantum chemistry to create new kinds of molecules, and he designed a new light-emitting molecule for the company to pursue.

He said he learned just as much outside the office as during work hours. He explored the Kansai region on weekends, often by himself. He had learned enough Japanese to get by and found that just making the attempt to speak the native language earned him vast amounts of patience. The question that seemed to unlock Japan: Sore wa dōiu imidesu ka?

(Translation: What does that mean?

)

I asked that everywhere,

he said.

Napoleón Nasta-Terrazas documents his time in Japan. Courtesy of Nasta-Terrazas

One day, while visiting Mitaki-dera, a mountainside temple just outside Hiroshima, he hiked up a trail for a better view of the sunset. On his way out, he found the temple gates locked. An employee spotted him and berated him, clearly accusing him of trespassing. She grew increasingly angry at his lack of answers until he threw up his hands in desperation, as if surrendering, and said in Japanese, Sorry, sorry, sorry, you’re speaking too fast, I can’t understand you.

The woman’s demeanor softened immediately. She appreciated his attempt to meet her on her terms. Rather than call the police, she politely escorted him out.

It was like I passed her test,

he said.

Living and working abroad helps finetune important technical skills like communication, Wilkins-Versalovic said. They are difficult to teach in a classroom but important to unlocking professional doors. She cautioned against viewing internships as just a key to a bigger paycheck. Many young engineers want to work on the world’s most pressing issues — and the better the resume, the better the chance of finding meaningful work, she said.

Kenya

Elena Talarico Ribeiro’s nerves flickered like the lights of the nearby school building.

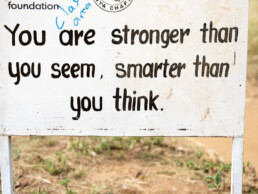

Night was falling over the southwest Kenya countryside. Talarico Ribeiro and her fellow students had finished installing a small solar panel system at an all-girls boarding school about 30 minutes’ drive from the nearest town. At the lighting ceremony, the boarding school’s students read poetry and performed ancestral dances while Talarico Ribeiro and other UT students served dinner. As the lights flickered with each test, the Kenyan students grew increasingly excited, leading Talarico Ribeiro to slowly grasp the importance of power to that school, where students rose at 5 a.m. to catch the daylight and rarely read past sunset because of the strain on their eyes. At last, the lights came on and stayed on. Talarico Ribeiro found herself overcome with giddy laughter and tears.

I struggle with questions like, ‘should I go to law school’? They have signs that read ‘Say No to GMS,’ which means genital mutilation surgery,

Talarico Ribeiro said in an interview. When the lights came on, all of a sudden, what we were doing, why we were doing it, it made sense in a way that really overwhelmed me.

Kumar, the water resources professor who led the expedition, watched the ceremony proudly.

“The technical excellence the students displayed in building the solar grid was remarkable. But the thing I’m most proud of is the bond between the Kenyan students and our students.”

— Manish Kumar, professor, Maseeh Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering

Their experience is part of a budding partnership between the Cockrell School and GivePower, a nonprofit that brings clean water and energy projects to underdeveloped communities around the world. The partnership with UT can be traced to GivePower founder Hayes Barnard’s 2022 move to Austin. Barnard and UT president Jay Hartzell soon began discussing ways to give students hands-on opportunities to learn about sustainability.

Those talks led to the inclusion of Kumar, a renowned expert in water management and purification systems and a professor in the Cockrell School’s Fariborz Maseeh Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering. For the first few days in Kenya, Kumar and his nine students dug trenches and wired panels, living in tents at the boarding school. Its students are between 14 and 22 years old, close to the ages of the visiting Longhorns.

There were cultural differences, of course.

They asked me if I had a husband. I said no. They looked at me like I was crazy. I looked at them like they were crazy,

Talarico Ribeiro recalls.

The similarities struck her even more. The boarding school students wanted to be doctors, lawyers, politicians. Many spoke more refined English than their UT counterparts. They were excited that, with a stable source of electricity to power internet service, they could peruse TikTok.

They just want a little more; just like anyone would,

Talarico Ribeiro said.

For the second half of the four-week trip, the UT students traveled to Wote, where they split into groups to conduct different types of research. Some surveyed community members. Others produced water safety materials. Three students worked with Kumar to develop a water treatment system to improve the local groundwater, which is often rendered undrinkable by heavy concentrations of harmful metals and minerals.

Kumar aims to help GivePower package this research to deliver solar-powered treatment facilities that produce water cheaply enough to compete with the groundwater wholesalers many Kenyans rely on. Schools and villages could sell the water — which, unlike the wholesalers’ supply, is treated — and use the proceeds to maintain the system. The ultimate goal is solving one of Kenya’s most pressing public health issues: reliance on water so dirty that it is, as Barnard once put it, poisoning millions of people who have no alternative for drinking, cooking and bathing.

A one-time President’s Award for Global Learning grant boosted this long-term goal. That funding allowed Kumar to broaden the experience by including two professors, Lucy Atkinson and Patrick Bixler, who taught students about environmental advocacy and policy, respectively. Kumar said he is looking for sponsors to continue the broader scope that the President’s Award enabled. That scope allowed organizers to include students who are not engineering majors, thereby fostering the sort of interdisciplinary cooperation required to pull off complicated, difficult projects, said Daniel King, Kumar’s graduate research assistant.

Courtesy of GivePower.

Thus Talarico Ribeiro, 21, joined Kumar’s group despite lacking an engineering background. She is triple majoring in sustainability, geography and international relations. At GivePower’s test site, a plot of open land near a river, she helped bolt pieces into place and mixed quicklime for the treatment system, which removes minerals from groundwater. It was a lesson in the day-to-day realities of fieldwork. Many of the system’s parts did not fit. Kumar and King sometimes had to halt work for hours while one of the GivePower assistants or graduate students from a nearby university found a suitable piece. National protests over unpopular tax increases also led Kumar to ask the students to stay in their hotel for a few days, though Wote remained safe.

When it came time to return to Texas, 75% of the water pulled from the ground was being fully treated, King said — an extraordinary level of efficiency.

Talarico Ribeiro is still trying to help with Kenya’s water problems. She is now compiling data from 11 of GivePower’s test sites in Kenya to create maps showing correlations between underground rock formations and water quality.

“We were so lucky to be able to help people on this trip,” she said. “I still want to help.”

— Elena Talarico Ribeiro

Greece

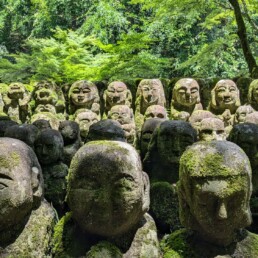

The camp itself wasn’t what surprised Eichelberger.

He knew, thanks in part to a short course on camp management, that these camps don’t actually look like the stigmatized tent cities so often featured on international news. The camp visited by the Cockrell students, near the coastal town of Thessaloniki, represents a second step that refugee families, mostly Afghans, made after an initial round of resettlement.

The 450 residents live in air-conditioned shipping container homes arranged in neat rows. Still, the accommodations were spartan, leading Maria Drakaki, a professor of humanitarian engineering at the International Hellenic University, to reach out to colleagues at UT, where she earned a Ph.D. in physics and maintains connections. Perhaps Cockrell students could make the camp a bit brighter.

What surprised Eichelberger was how bright residents had already made the camp. They filled tight, otherwise drab spaces with flower beds and gardens. Children chased well-fed, playful dogs. The concrete wall encircling the camp on three sides was covered in murals. A chain-link fence along the fourth side allowed a view down a hillside to a lake.

The little things they did made a huge difference,

said Eichelberger, a junior studying environmental engineering.

Shortly after entering the camp, Eichelberger and one team of students began measuring the roughly 20-meter-long, heavily eroded strip set aside for the playground. A second team headed off the curious children, occupying them with hula hoops and jump ropes. One group of girls made us play Ring-Around-the-Rosie so many times,

said Zaheer, the mechanical engineering major.

Over three hours, a realization crept in among the students measuring the terrain.

We couldn’t give them their dream playground. There just wasn’t enough space for that,

Eichelberger said. It turned out like a lot of projects: not everything goes your way.

The disappointment quickly vanished amid another surprise, one that upended a fundamental assumption.

Camp residents did not even want a playground.

That was shocking to us,

Zaheer said.

The revelation surfaced after days of focus groups with residents. Through a translator — who accepted the role mainly because no one else spoke enough English and Farsi to facilitate a dialog — residents reflexively claimed they wanted something for the children. But the children already had two playgrounds, albeit highly worn ones. The long, narrow, crowded camp afforded few opportunities for adults to maintain their own health.

The adults really wanted a gym. They clarified their wants by circling different types of equipment on paper questionnaires.

It was probably not the way it would have happened over an email,

Zaheer said. If we hadn’t taken the time to talk with them, we wouldn’t have learned what they really wanted.

The residents still may not get it, said Janet Ellzey, the faculty lead and a professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering. She cautioned that changes to the camp must go through its management, the Greek government and possibly other layers of approvals. Other priorities may emerge. This is perhaps the most pertinent lesson, said Ellzey, the director of the Cockrell School’s Humanitarian Engineering program and someone who, two decades ago, as an assistant dean, oversaw IEE’s creation: humanitarian aid programs should temper enthusiasm with humility. Not all problems are engineering problems.

Sometimes it’s just out of your hands,

Ellzey said. You have to learn to accept that.

The project, per Ellzey’s plan, has been handed off to Texas Global’s Projects with Underserved Communities program, which will handle next steps. Ellzey’s students returned to the Forty Acres to continue their engineering education. Zaheer, who is preparing for a career in robotics, said the biggest surprise — that the residents wanted something different than they assumed — affirmed her desire to work directly with the people her skills will help, crafting solutions to their specific needs. Two conversations in particular stuck with her.

The first came with the camp translator. He had, coincidentally, been training to be an engineer when he fled Afghanistan. He is now in his late 20s or early 30s, as Zaheer recalls. She remembers him saying, “I had a lot of potential, didn’t I?” Past tense.

As she recounted that conversation, the empty conference room where she sat rumbled from the vibration of an engine test happening at a nearby test stand on the SpaceX campus in McGregor. She was finishing a summer internship there, helping to test rockets. If not for her mother’s decision to emigrate from Pakistan to the United States in search of a better life for her family, she would probably not have had such an opportunity.

Zaheer speaks Urdu, which allowed her to talk in the refugee camp with a mother and young daughter. Much of their family is in Pakistan. Zaheer saw, in that mother, a younger reflection of her own. In the daughter, a reflection of herself.

“Hearing her talk about how she wants to make a better life for her kids … I teared up on the ride back. I still tear up about it sometimes.”

— Eman Zaheer, senior, Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering

INTERESTED IN THE INTERNATIONAL ENGINEERING EDUCATION PROGRAM?

Email IEE staff at iee@engr.utexas.edu, book an appointment with a staff member, peruse the website or drop by one of the informational sessions.