ASE Distinguished Alumna Jeannie Leavitt set a course for future generations of female fighter pilots, including members of the Marvel Universe.

By cody bowie

At the Pentagon, three women stand on stage, their faces lit by the burst of flash bulbs. Then Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Merrill McPeak gathered them to make an historic announcement: effective immediately, women pilots and navigators will be able to compete for, train in and fly any aircraft in the inventory of the United States Air Force. The date: April 28, 1993.

The women are stoic, fluent and confident in their responses to a barrage of questions: What does it mean for you to fly an F-15E Strike Eagle? Why would you ask for such a thing? How many men are you leapfrogging who are waiting for the very combat training that you are now going to be getting? Will women fighter pilots be asked to refrain from getting pregnant? Can women really be warriors?

If you ask Jeannie Leavitt about this day, she’ll tell you that it isn’t what she wants to be remembered for. She has never cared about being the first female fighter pilot — only doing her best.

Once we started flying, people began to see we were there because of our abilities and not our gender,

Leavitt told the Associated Press in 2012. I don’t see it as a ‘first sort of thing.’ I see it as an incredible opportunity.

Jeannie Leavitt (B.S. ASE, ’90) is the first woman to serve as a fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force. She was named a 1997 Outstanding Young Alumna and a 2023 Distinguished Alumna by Texas Exes. She blazed a trail for future airwomen. Her drive to try new things has led to many accomplishments — from interning with NASA, to becoming the first woman to command a U.S. Air Force combat fighter wing to consulting on the 2019 film Captain Marvel.

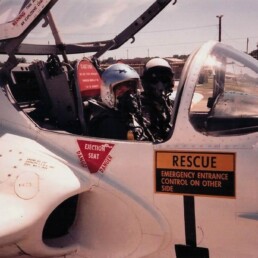

Leavitt during Field Training Camp for Air Force ROTC at UT Austin. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

Photo Credit: SSgt Ryan Sanders/U.S. Air Force

Photo Credit: SSgt Ryan Sanders/U.S. Air Force

Aiming Sky High

The third of four sisters, Leavitt’s interest in flying began on the ground. Her mother was afraid of flying; so afraid that years later, she would take a 1,000-mile train trip to watch her daughter graduate from flight school.

We would always drive our family van, or take the bus or the train. We never flew on airplanes,

she says of her childhood.

But she remembers watching airshows as a kid, craning her neck to see planes flit and dive in practiced parabolas. Her first commercial flight came at age 18, a trip to visit her uncle in Albuquerque.

I loved the whole concept,

she says of that first flight. How does this big heavy aircraft go up in the air? I was fascinated by the ‘how’ of flying.

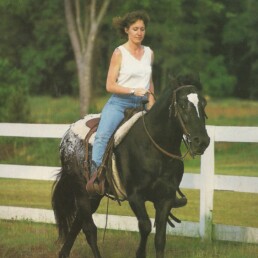

There was another draw to being airborne, too, something Leavitt recognized from her years of riding horses — a feeling of freedom. She began riding with her Girl Scout troop and bought her first horse when she was around 16.

I didn’t have a lot of money, so my options were an older horse with bad habits or a young horse that wasn’t trained. And I ended up buying a three-year old appaloosa stallion who had never been successfully ridden.

Smokie stayed with her for 26 years, traveling with Leavitt to college, graduate school, and from base to base throughout her Air Force career.

Leavitt poses with fellow students during her Air Force ROTC Commissioning. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

Smokie went everywhere Leavitt went during their 26 years together. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

I would say courage was a learned trait for me. I was probably always bold. I was competitive and I was driven, but the courage part I think I learned through horseback riding. I learned literally that when you get thrown off the horse you’ve got to get back on. Smokie threw me off a few times.

After graduating high school, Leavitt followed her sister to the University of Missouri-Rolla (now the Missouri University of Science and Technology). But after just one year, she set her sights on The University of Texas at Austin. There was this draw for me to come to Texas,

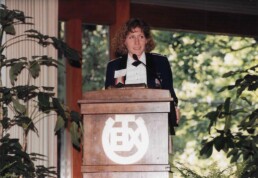

she said in her 2023 Texas Exes Distinguished Alumnus acceptance speech. There was something about the aura of the state. Well, the University of Texas had a great reputation. There was an excellent aerospace engineering department. And of course, the Texas Longhorns.

So, Leavitt packed up her Ford Mustang, asked her parents to send Smokie behind her, and drove to Texas. She knew she wanted to study aerospace engineering, but that was it. Leavitt estimates that women made up only about 10% of UT aerospace students at the time. Even more daunting, Leavitt remembers arriving at Frank Erwin Center to build her class schedule (a process known as adds and drops

) and seeing more students there than she saw during her entire year at the University of Missouri-Rolla.

Leavitt says the things she learned in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, as well as her experience in the Air Force ROTC and the Texas Intercollegiate Equestrian Team, built in her a confidence to try new things.

One such experience came through a UT co-op program with the Johnson Space Center in Houston, where a chance encounter with an Air Force second lieutenant waiting for pilot training changed the trajectory of her life. I had never been behind the controls of an airplane. I just decided I wanted to be a pilot.

Leavitt’s first dream was to be a NASA Astronaut. Pictured here, she participates in a UT co-op program with the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

“My decision to go to The University of Texas at Austin completely changed my world. This university teaches strength of character and builds the innovative leaders of tomorrow. UT students learn lessons about creative thinking, about courage and about compassion, and these lessons served me well in my Air Force career.”

Before: 1st Lt. Jeannie Flynn, the first F-15E female pilot, sits in the cockpit as she performs engine start. Flynn will be assigned to the 555th Fighter Squadron for six months of tactical training. Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Brad Fallen/U.S. Air Force

After: U.S Air Force Col. Jeannie Leavitt, 4th Fighter Wing commander, signals her crew chief before taking flight at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, N.C., July 17, 2013. After being stood down for more than three months, the 336th Fighter Squadron was finally given the green light to resume flying hours and return to combat mission ready status. Photo Credit: Airman 1st Class Brittain Crolley/U.S. Air Force

Beyond the Forty Acres

After graduating from UT in 1990, Leavitt moved to California where she received her Master of Science, Aeronautics and Astronautics degree from Stanford University in 1991.

Later that year, Congress voted to repeal the law that prevented women from flying in combat aviation. The military, however, remained in a holding pattern. The Department of Defense set up a two-year study on women in combat to gather more information. Women still weren’t sitting in the cockpit of fighter planes.

I knew it wasn’t if but when [women would be allowed to fly fighters], but I didn’t know if it was going to be months or years.

Air Force assignments drop in batches, and pilots can request their preferred aircraft from the available pool. In 1992, Leavitt was the top Air Force graduate, ranked No. 1 in her class, meaning she got first pick of the available planes. On stage, in a room full of almost entirely men, she requested to fly a F-15E Strike Eagle — the most advanced fighter plane of its time with unmatched maneuverability, range and acceleration.

She was told no. Leavitt settled for a KC-10, a tanker and cargo aircraft. A few weeks later, however, she was given the opportunity to be a T-38 instructor pilot and moved from California to Oklahoma, with Smokie not far behind.

My assignment changed a few times. In hindsight, it allowed me to remain eligible to go fly fighters.

She was training at Randolph Airforce Base in San Antonio a few weeks later when she got a surprise call from a three-star general at the Pentagon. I was just in my room heating up lunch and he called and started asking some questions.

Their conversation went something like this…

When you asked to fly a fighter, did you actually want to go fly it? Or were you just trying to make a point that women could fly fighters?

the general asked.

I absolutely want to go fly it. I’ve flown in the backseat of an F-16 five times — I absolutely want to fly fighters,

Leavitt responded.

If you did, you would be the first woman. There’d be a lot of attention and a lot of publicity.

I don’t really want any of that. I don’t care about being the first; I just want to fly fighters.

The general paused. For a moment, all Leavitt could hear was the soft sizzle of her lunch on the stove. That’s not an option,

the general finally said. If you go, you’ll be the first.

Leavitt responded without hesitation. I’d much rather be number 43 when no one cares, but if those are the terms of the deal, I’ll take it!

Oh no, nothing’s changing. Go back to training,

the general replied hastily, and hung up.

After that call, Leavitt checked her landline every day for messages. And finally, in mid-April of 1993, she was called into a four-star general’s office and told that she would be flown to the Pentagon the following week for the announcement. They told her not to tell anyone, and she didn’t — not even her parents.

She and two other pilots, Capts. Sharon Prezler and Martha McSally, underwent extensive media training in the days leading up to their press conference on April 28 — the one where Leavitt was catapulted onto the national stage. And the publicity didn’t stop after that day.

There was quite a bit of pressure at the beginning of my career [to do publicity] — I was directed to do so and I really did not want to attention because it really made it hard to be a part of the squadron and blend in.

Leavitt poses with her F-15E Strike Eagle in February 1994. Photo credit: U.S. Air Force.

Leavitt in a T-37 during Field Training Camp for Air Force ROTC at UT. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

Initially, Leavitt felt she had to prove herself again and again to be seen as an equal with her male counterparts. Once she was finally able to prove her competence, however, she was quickly accepted. And her unique perspective was a strength she brought with her to every meeting and assignment.

“I think that having diversity of thought in an organization makes the organization so much stronger.”

Leavitt would go on to become not only the first female fighter pilot, but also the first female fighter pilot to complete and later instruct at the weapon’s instructor course. As a colonel, she became the first woman to command a U.S. Air Force combat fighter wing. Her last position before her retirement in 2023 was as the Department of the Air Force chief of safety at the Pentagon and commander of the Air Force Safety Center at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico.

Leavitt speaking after receiving the Outstanding Young Texas Exes award in 1997. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

Brie Larson gets hands-on help from Brig. Gen. Jeannie Leavitt, 57th Wing Commander, on a trip to Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada to research her character, for the film, Captain Marvel.

Photo Credit: Brad Baruh/Marvel Studios

Star Power

Leavitt’s marvelous accomplishments got the attention of Hollywood as they sought to bring another heroic female flyer to the big screen, Carol Danvers. The makers of the 2019 film Captain Marvel

sought her out to share experiences as a consultant, helping the directors and actress Brie Larson hone the depiction of main character Captain Danvers.

Someone called up from our public affairs Hollywood office and asked me if I would speak to them and I said, ‘no thank you.’ Because I had had so much publicity in 1993. I just wanted to stay out of the limelight, the spotlight,

Leavitt says.

But a friend convinced her that her lived experience of being the first female fighter pilot would be invaluable to the role. So, she hosted the movie’s directors at Nellis Air Force Base, where she was stationed at the time.

It was so much fun. We were laughing, they were asking different stories about my life and towards the end they said, ‘You are nothing like we expected.’ I think because fighter pilots in movies are portrayed as abrasive, arrogant, very aggressive. And I said ‘Oh no, I will be very nice — on the ground. I go up there, whole different set of rules.’

Advice she gave shaped Brie Larson’s performance, including details like the proper hand to carry her helmet bag in — the left — so she could salute the crew chief with her right hand when she approaches an aircraft.

The cast of “Captain Marvel” pose with Leavitt. Photo from Leavitt personal collection.

Having recently moved back to Texas, you’ll still find Jeannie Leavitt riding horses and flying — but she’s excited to start a new chapter of her story. She’s in the early stages of building her own company, Leavittate.

I have started consulting and speaking. One of my focus areas is to help people feel empowered. I’ve heard people say, if you can see it, you can be it. But the problem in my case was that there was no one to see. So, it’s almost along the lines of visualizing. If you can see the invisible, you can do the impossible.

She also says that, if NASA’s hiring, she’s interested. I always wanted to be an astronaut. I’m still willing. If they’re looking, I’d still be an astronaut!

Leavitt says her wish for women studying aerospace engineering is that they believe in themselves.

“Too often as women, we feel like have to be perfect. We don’t have to be perfect, just be brave and try new things. When there’s opportunities, give them a try. My entire path was opportunities presenting themselves that I’d just try. Not everything’s going to work, but try everything. Be brave.”

PHOTO CREDIT: SSGT RYAN SANDERS/U.S. AIR FORCE