When John Goodenough licensed one of his most important recent discoveries — a next-generation, solid-state battery — to Hydro-Quebec earlier this year, it continued a quarter-century trend of the Canadian electric utility commercializing products created by the 2019 Nobel Prize winner. Just days later, it was revealed that the technology will become an integral part of Mercedes-Benz’s electric fleet, yet again reinforcing Goodenough’s influence in the continued advancement of battery engineering.

But Goodenough is far from the only faculty member in the Cockrell School with a record of turning research breakthroughs into tangible products that advance industries. The Cockrell School’s impact on innovation at The University of Texas at Austin is immense, with faculty and students responsible for roughly two-thirds of all startups, patents and licensing deals to come out of UT over the last decade.

The Cockrell School has been a major driver of innovation at UT for years now,

said Van Truskett, executive director of UT’s Texas Innovation Center and a Cockrell School staff member. Ultimately, the goal of our research is to get products into people’s hands and make sure we are doing something useful for society.

The journey from an idea, to funding, to experimentation and to publishing a paper can be a long one. But in many cases, that’s really just the beginning. Along the way, researchers face a variety of important decisions — chief among them, whether to license their technology to a company, as Goodenough did with his latest battery discovery, or take on the challenge of building a startup of their own.

Leading the Way at UT

UT’s Office of Technology Commercialization asks faculty working on papers to file invention disclosure forms as their projects get close to being published. The office receives about 130 to 160 of these forms per year, and faculty in the Cockrell School typically account for 65-75% of them, underscoring the school’s impact on creating new technologies.

Here’s a look at the prolific work of Cockrell faculty and students in recent years:

Pushing Beyond the Published Paper

Breakthrough research can garner global attention for the teams and labs that develop it, and for the school in general. However, plenty of research promising big changes never actually makes it to market.

Sometimes, that’s because it’s hard to turn an experiment into a tangible product. Other times, the researcher wants to move onto the next project.

We always push the frontiers in academia, but if you leave your research in the paper and stop there, it won’t go anywhere,

said Adela Ben-Yakar, a professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering.

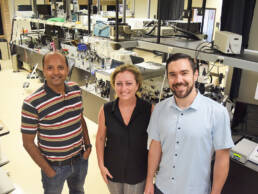

In 2016, Ben-Yakar decided not to stop when the paper was published, creating Newormics to commercialize her drug-discovery research. Earlier this year, Newormics received funding from the National Institutes of Health Small Business Innovation Research program to perform advanced testing on HIV anti-viral drugs.

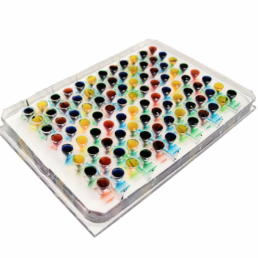

Most testing today uses either single cells, which don’t always paint the full picture, or animals, a process that produces superior results but is controversial. Newormics provides a middle ground for screening everything from pharmaceuticals to agricultural products to cosmetics, using 1-millimeter-long roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans). The worm represents a good analogue for how products might affect humans because they share roughly 60-70% of the same genes and have a full nervous system.

Ben-Yakar, who continues to work as a full-time professor, also serves as CEO of Newormics, working there about one day a week. Several students and former students help run the company, including Evan Hegarty, co-founder and director of manufacturing. If her students hadn’t shown interest in turning the research into a company, Ben-Yakar said the research might never have advanced beyond the published paper stage.

Delia Milliron, a professor in the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering (and also the incoming department chair starting in January), has juggled the duties of researcher and startup founder not once but twice.

Milliron’s first startup, Heliotrope Technologies, makes windows that tint on demand using nanocrystal technology. Milliron has since stepped back from that company, giving up her board seat at the venture-backed startup to free herself up to continue researching the glass technology and pave the way for her second startup, Celadyne Technologies.

Celadyne makes materials for hydrogen fuel cells, an alternative to batteries that convert hydrogen to electricity and power a variety of things. An experiment with little practical application but important scientific ramifications served as the impetus for the company: how protons move through nanocrystal films. One of Milliron’s students combined the film with a polymer, which led to a major improvement in conductivity and paved the way for the startup.

The co-founding student, Gary Ong, is now CEO of the company. Though he and Milliron were both initially skeptical of hydrogen fuel cells, they came around to the technology because of the benefits of longer charges and cleaner energy over traditional batteries. So, they decided to make hydrogen fuel cells the focal point of their material.

Both of Milliron’s startups focused on new materials. She chose to spin off companies because of the challenge of finding a licensing partner that has both the appetite to take on a new material and the engineering know-how to make it work.

It makes sense to me to start a company when the material can’t be easily plugged into existing processes,

Milliron said. And with anything coming out of our engineering labs, we have the technical chops and know the technology on the ground better than anyone else because we came up with it.

The Next Big Thing

Faculty and students are hard at work across the Cockrell School performing groundbreaking research and turning those ideas into tangible products.

Here are six emerging startups that commercialization personnel identified as companies that could make a big impact in the near future:

Co-founded by Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering professor Arumugam (Ram) Manthiram and researchers and mechanical engineering alumni Evan Erickson and Wandga Li, this startup aims to eliminate cobalt, an expensive and politically challenging element, from high-energy lithium-ion batteries that power personal electronics, electric vehicles and more.

This startup takes engineered meat to a new level. Co-founded by professor Janet Zoldan of the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Katie Kam, BioBQ makes customized cell-based meat that has the texture and consistency briskets, steaks and other meats. Eventually, BioBQ meats will be able to be loaded with vitamins and nutrients specific to customers’ dietary requirements.

A reimagined way for young families to feed their babies and co-founded by Lydia Contreras, assistant professor in the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, and McCombs Business School and Texas Law alumna Dara Chike-Obi, the startup aims to offer home delivery of its cognitive developmental infant feeding system with antimicrobial properties.

The leadership team of this startup, which includes Chris Rylander, professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, John Uecker, interim chief of the Division of Minimally Invasive Surgery at Dell Medical School, mechanical engineering alumni Christopher Idelson, and Doug Stoakley, built a disposable laparoscopic lens cleaner. The company recently received FDA approval for the device, which can clean surgical scopes while inside the patient, eliminating the need to remove them for cleaning several times during a procedure. The startup recently raised $2.6 million in new funding.

A data security platform for large enterprises that gives companies greater visibility and control over their critical information in storage services. The startup is led by Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering’s Mohit Tiwari and Ph.D. student Casen Hunger. It officially launched earlier this year and raised $3 million in seed funding.

This startup makes a robotic rehabilitation system that helps patients with brain or spinal conditions improve control of their arms. The four-year-old company raised $2.5 million in May, and it was co-founded Ashish Deshpande, an associate professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering, and mechanical engineering alum Youngmok Yun.

Launching a Startup Vs. Licensing the Technology

Ben-Yakar considered licensing the technology behind Newormics but ultimately decided to develop it on her own because she thought there was an urgent need for the product right away. The time it would take to license it and impart the knowledge developed by creating it was just too much, she thought. And there was always the risk that someone else wouldn’t be able to achieve the same results.

However, over the last decade, Cockrell School researchers have largely opted to license their technologies to existing companies rather than build their own startups. The number of license deals from 2010 to 2019 tripled the number of startups formed, according to data from UT’s Office of Technology Commercialization (OTC).

The researchers who decide to license their discoveries typically want to stay on the academic side and focus on the fundamental innovative research they’re doing, and they don’t want to expand their efforts and time into the business side of things,

Truskett said. And then we have faculty members who are curious and interested in both the academic hat and the business hat that they could wear.

Aside from the desire to try the business leader hat on for size, the main reason a researcher might spin off a startup is that no one is doing what they’re trying to accomplish. There’s no logical partner to license with.

As the research progresses, OTC works with faculty to target a specific market need and help decide whether they want to license their technologies or start a company around them. Then it helps them identify investors or potential licensing partners.

The main driver for forming a new company is something that is a truly revolutionary technology concept or a revolutionary new way to use a technology that will really change the way things have been done in the marketplace,

said Les Nichols, director of OTC.

A license makes more sense, Nichols said, when research finds a new use of an existing technology or optimizes something that moves the needle but doesn’t upend how things work.

Starting a new company from scratch represents a more challenging path but gives researchers the chance to control and grow their research. The Texas Innovation Center, located in the Cockrell School’s Engineering Education and Research Center and co-led by the College of Natural Sciences, helps these budding entrepreneurs get the resources they need to build a company, including everything from taxes and accounting to pitching investors to product development to sales and marketing.

Milliron, who has learned a lot from her experience in the startup world, offered two key pieces of advice to researchers looking to spin out their discoveries into new companies: think critically and know your market.

“Be very critical about the market opportunity and the need for the technology you envision. Don’t assume the world needs your technology. Or that the market you had in mind when you first developed your technology is the one that will allow you to advance it to commercialization.”

—Delia Milliron