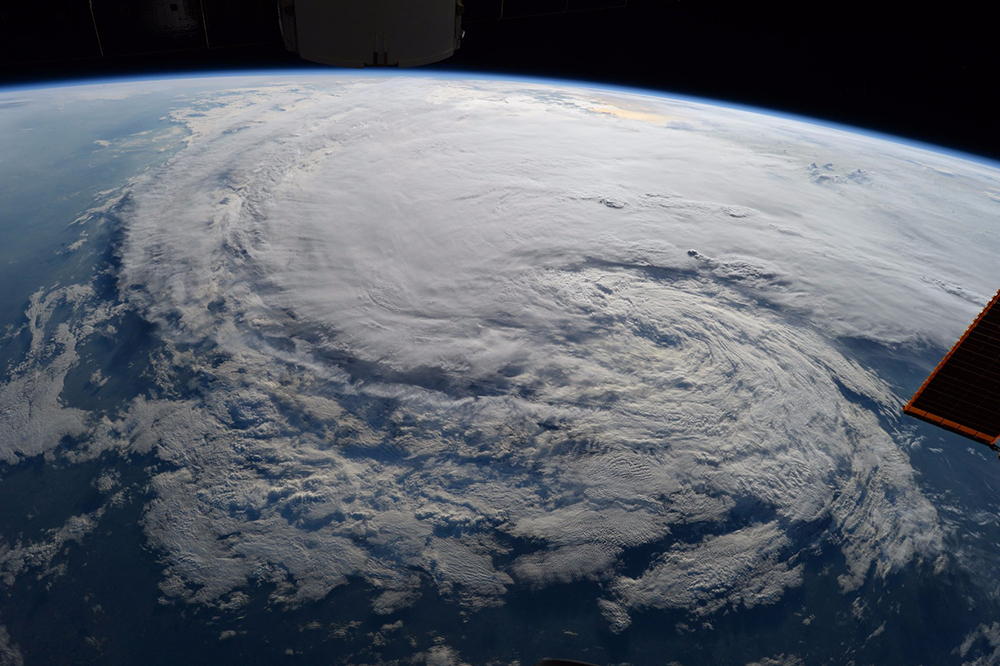

One year after Hurricane Harvey dumped 60 inches of rain on Houston and Southeast Texas and shook the Lone Star State to its core, some coastal towns may never be the same again. In terms of scale and impact, it was truly a storm like no other. And through it all — even well after it was gone — Texas Engineers were there searching for solutions.

Because of UT’s unique breadth of research quality, and because of its location and the array of different landscapes and climates across the state of Texas, the university has become a recognized leader in research efforts that analyze weather patterns and prepare cities and emergency response units in situations like we saw in Houston.

At one point, there were 85 rescue helicopters over the sky. And hundreds of thousands of people from across the United States and around the world either donated money or traveled to Texas to help on the ground. If that isn’t inspiring or isn’t cause for optimism for the future, I don’t know what is.”

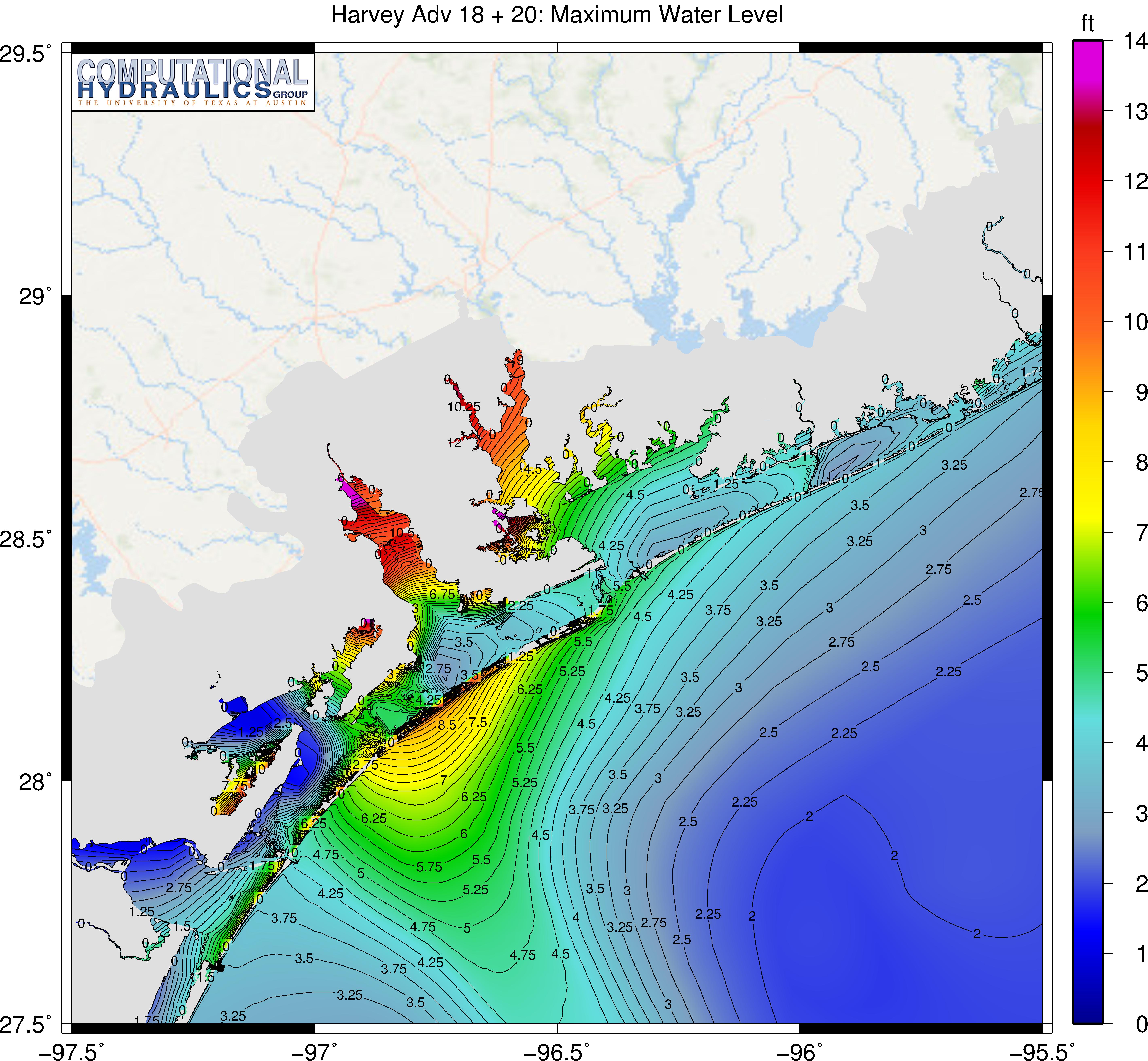

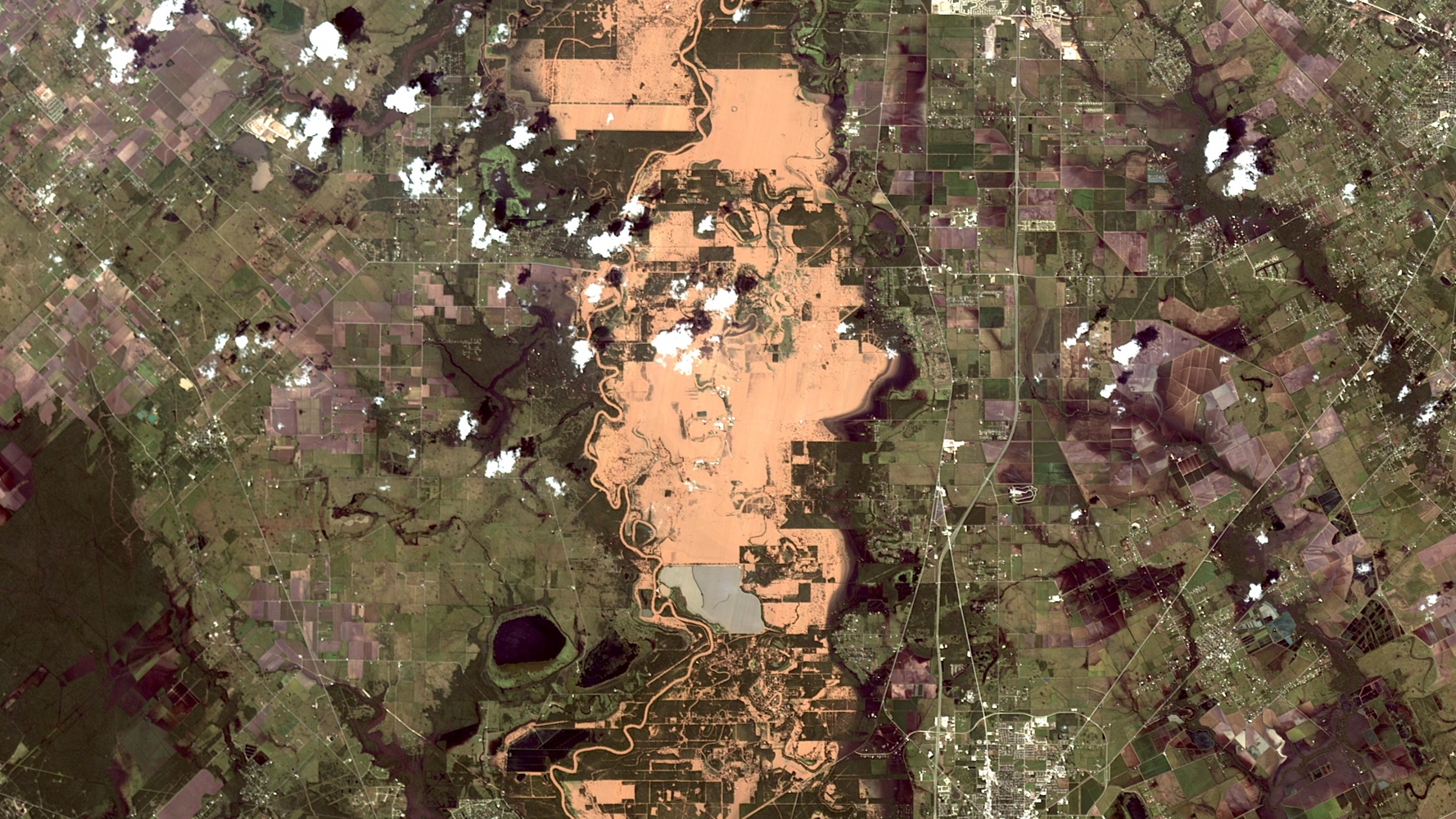

Clint Dawson, professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics and the head of UT’s Computational Hydraulics Group, developed storm surge prediction models (storm surge is typically the part of a major storm that does the most damage) that were integral to estimating the catastrophic potential of Harvey. In addition, researchers in the Center for Space Research deployed their satellite imaging technology to paint a clearer picture of what was happening, while Davide Maidment, recently retired professor in the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering and one of the world’s go-to experts for surface water information systems, was a key adviser to response units on the ground.

And underpinning everything was the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), home to several of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, which allowed researchers to collect, store and analyze massive amounts of storm data quickly, revealing the extreme scale and behavioral pattern of the hurricane.

Today — after assessing the aftermath and working to help victims put their communities back together — UT engineers and scientists are focusing on the question most critical for Houston’s future: How can we be better prepared for the next Harvey-like storm?

They believe the answer lies in the data.

“David Maidment approached us at TACC to help develop the first-ever tools for modeling conditions on the ground during a storm — in real time,” explains Niall Gaffney, director of data intensive computing at TACC. “He thought that if we could combine all available data on local topography with observed and predictive weather models for the storm in both short and long terms, his team could gauge where and how high the water could be.”

While the idea was certainly useful (in some cases it accelerated the reaction times of first responders), there wasn’t quite adequate topographical data to provide the detail needed to aid emergency rescue operations at the level they were hoping for during Harvey. But the exercise was not in vain. With each major hurricane that arises on the Gulf Coast, new lessons are always presenting themselves. Compiling and analyzing data to develop efficient, effective and universally applicable response protocol is only made possible through experience.

“Now, over 180,000 square miles of the state of Texas are currently being mapped in unprecedented detail,” Maidment said. “That’s a major component of accurate flood mapping for the future. If we can effectively follow the motion of the water more precisely, it is a huge step forward.”

Back in 2005, Bob Gilbert, professor and chair of the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, was part of an expert team that reviewed and assessed all forensic analysis gathered by the federal government after Hurricane Katrina. When compared to Harvey, which killed 80 people, destroyed an estimated 300,000 vehicles and damaged over 200,000 homes, Katrina was an even bigger disaster. But it also provided crucial information that would end up helping responders during Harvey.

“The majority of the 1,800 people who lost their lives during Katrina were over 65 years of age,” Gilbert said. “These victims were of all races and socioeconomic backgrounds. It didn’t matter which neighborhood they lived in, and it wasn’t about being rich or poor. Realizing this, it was clear that Harvey’s emergency response teams needed to prioritize elderly populations during their operations, which made a big difference.”

The scale of Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey were extraordinary, and the hardships that victims have endured since have been nothing short of devastating. But as we’ve seen time and again after natural disasters, these experiences have a way of bringing out the best in people.

“With Harvey, at one point there were 85 rescue helicopters over the sky,” Maidment said. “And hundreds of thousands of people from across the United States and around the world either donated money or traveled to Texas to help on the ground. If that isn’t inspiring or isn’t cause for optimism for the future, I don’t know what is.”