Two years ago, the Cockrell School community watched as its outdated Engineering-Science Building — a relic of the days of chalkboards and vacuum tubes — crumbled to the ground in a pile of rubble, making room for the Engineering Education and Research Center (EERC). It was September 2014, and the transformation of engineering education on the Forty Acres was just beginning.

In today’s workplace — where a colleague in Singapore is just a video chat away and a complex machine part can be fabricated using a 3D printer in a matter of hours — the role of the engineer is much different from even a decade ago. To thrive in industry, engineering students need to learn more than just the technical fundamentals — they must also gain strong communication and problem-solving skills, as well as be prepared to lead diverse teams, all in four short years.

From changes to curriculum across all majors, to increased opportunities for leadership development, to the opening of a new makerspace, the Cockrell School is creating an educational culture centered on student projects and multidisciplinary collaboration.

And when the 430,000-square-foot EERC opens next year, Texas Engineering will have a state-of-the-art facility for a new era of engineering education.

“This building will change everything,” said Dean Sharon L. Wood. “Our students will be able to work on more projects and share ideas in open, architecturally stunning spaces. And — for the first time in the Cockrell School’s history — students will have one building that is not tied to a specific discipline, where they can learn and collaborate with peers from every department. This multidisciplinary environment is essential if we want to expand students’ learning experiences.”

Space for Creating, Making and Doing

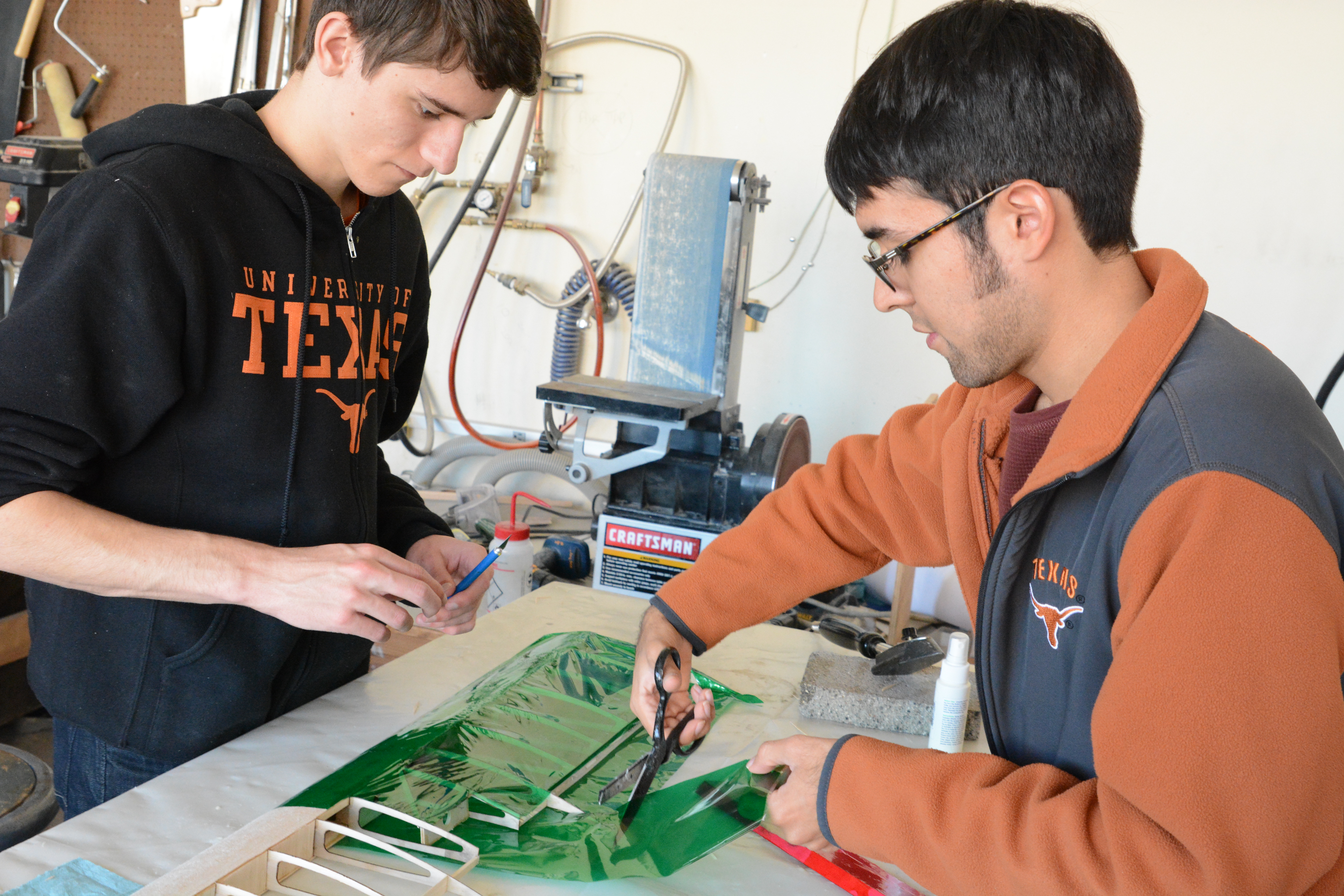

After more than two decades as a civil engineering faculty member in the Cockrell School, Wood understands that engineering students need a place to experiment, design and build. In fall 2014, she worked with mechanical engineering professor Desiderio Kovar to create the Longhorn Maker Studio, the university’s first dedicated makerspace for inspiring engineering student innovation.

Inside, students learn to push the limits. They break things and rebuild them. They develop their ideas and learn from their mistakes. They solve problems without textbook answers.

Equipped with the latest technologies, this makerspace provides 1,700 square feet of space where students can create prototypes for class or work on independent projects simply because they have an idea. With more than 7,000 student visits last year, it has become the undisputed hub for creative activity within the Cockrell School.

Since the maker studio opened, the school has added a wood shop and hired a new director, Scott Evans. Evans, who received his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from the Cockrell School, said the makerspace is crucial to helping students make the most out of their engineering education.

“I want to challenge freshmen to make something that works — to help students see themselves as engineers sooner,” he said. “When that happens, courses take on a new role for the students; they are more like resources to become better engineers.”

Next year, the maker studio will move into the EERC’s 23,000-square-foot National Instruments Student Project Center. With access to even more space, tools and technologies, students will be able to work on projects every semester. Through the center’s glass walls, everyone passing through the EERC’s atrium will see students hard at work on their creations.

“It’s time to take our students’ projects out of our basements, closets and hallways,” Wood said. “Everyone who visits the Cockrell School should see their incredible work and experience our community’s creative energy.”

Rethinking the Traditional Lecture

Formulaic problem sets and by-the-book lab reports are rare in industry. That’s why the Cockrell School is offering more opportunities for hands-on learning in the classroom each semester. One capstone design project during a student’s senior year just isn’t enough.

“By presenting students with open-ended problems throughout their education, we encourage them to communicate, to work together and to seek out new information and ideas,” Wood said. “Those are the skills they will need to succeed in today’s engineering careers.”

Across disciplines, faculty are reducing lecture time to focus on generating discussion and guiding students as they collaborate on projects.

Armand Chaput, senior lecturer in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, was recently recognized by the American Society for Engineering Education for his approach to teaching systems engineering through hands-on aircraft design projects.

“We are teaching systems engineering as a fundamental principle of design — not as a separate, theoretical subject,” Chaput said. “Once students see how systems engineering applies to and enables success in projects, they quit thinking about it as an abstract concept and start applying it to everything they do.”

Professors are also utilizing the Longhorn Maker Studio for class assignments. For example, students are building autonomous robots in electrical engineering’s Real-Time Operations course and designing miniature cars in mechanical engineering’s Machine Elements course.

The Cockrell School’s culture of entrepreneurship is a product of our tight-knit, creative community and our efforts to encourage more hands-on experimentation.”

—SHARON L. WOOD, DEAN, COCKRELL SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING

In preparation for the dramatic increase in project space in the EERC, Wood is supporting department-wide initiatives and allocating academic development funds to help faculty revamp their courses to focus on hands-on learning.

The Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering recently proposed a curriculum transformation to introduce more open-ended design courses and integrate liberal arts courses that strengthen students’ writing and communication skills. The Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering is working to enhance its educational model by leveraging new classroom technologies and hiring professors with industry experience to educate students on real-world challenges in oil and gas.

As the students’ academic experience continues to evolve, Wood is thinking about what’s next in engineering education, especially after encountering joint-degree programs between engineering and fine arts or liberal arts at other universities.

“Though it would be difficult to implement for a variety of reasons, I could see value in allowing students to design their own degrees that reflect their individual interests and goals,” Wood said. “As large-scale, open-ended projects become more and more a part of our students’ educational careers, this type of hyper-individualized education could really amplify those experiences.”

Maybe one day, no two Cockrell School students will graduate with exactly the same degree.

When Students Lead the Way

Some of the most exciting projects are initiated and led by students outside of the classroom. The Cockrell School’s more than 80 student organizations prove this every semester.

They act on their ideas by designing and building prototypes — like the planetary rover created by Women in Aerospace for Leadership and Development—and they compete in national and international competitions—like the team of biomedical engineering students who won first place for their low-cost patient monitoring device at Engineering World Health’s design competition.

Courtney Koepke, a biomedical engineering and Plan II senior who helped develop the device, said she learned the value of patience and communication while leading her team to success.

“The experience taught me the importance of having compassion for yourself and others. No one is perfect and, as a project leader, you have to trust your teammates to do their best — and ask for and offer help when needed,” Koepke said. “I’m so proud of not only our team’s success, but also how much each of us developed as individuals and as engineers.”

Student organizations and outside competitions also give future engineers the opportunity to partner with their peers in fine arts, liberal arts, business and natural sciences, teaching them new approaches.

For example, a team of three undergraduate mechanical engineering students partnered with a design student in the College of Fine Arts to create a traveling Disney attraction. The engineering students gained insight into user experience and the visual elements of the project, and the team’s attraction won second place in the Walt Disney Imagineering Imaginations Design Competition this past spring.

Cockrell School leadership hopes that the EERC’s student project center, ample meeting rooms and centralized student support offices will encourage even more students to participate in organizations and competitions.

Cockrell School leadership hopes that the EERC’s student project center, ample meeting rooms and centralized student support offices will encourage even more students to participate in organizations and competitions.

With a wealth of technology and resources in the Longhorn Maker Studio and a strong pool of talented peers across disciplines, students are also developing robust inventions that have the potential to turn into marketable products.

“The Cockrell School’s culture of entrepreneurship is a product of our tight-knit, creative community and our efforts to encourage more hands-on experimentation,” Wood said.

Today, students interested in entrepreneurship can enroll in the Longhorn Startup seminar, join UT Austin’s related student organizations and work with seasoned entrepreneurs and faculty advisors in the Cockrell School’s Innovation Center.

Whether working independently on a new prototype, leading a student organization or debating the direction of a class project, Texas Engineering students are gaining the skills they’ll need to thrive in industry and to truly change the world. As we look to the future, the Cockrell School will continue to strive to foster their talents and passions.

“Our students are fearless,” Wood said. “I want to provide them with the support they need to pursue their dreams.”